See also the entry for The Bromley Town Centre Park Trail, for the well, here.

St Blaise’s well was rediscovered in 1754 (by the Bishop’s domestic chaplain, a Rev Mr Hardwick); a worker showed him a spring, seeping into the moat (emptied of water, like all fishponds to be de-silted), which he identified as a chalybeate spring. It had buried ancient oak steps.

The spring is called “Chalybeate” because the water contains minerals, usually iron. There was a fashion for ‘Spa’ cures from about 1600AD onwards, so towns like Bath and Tunbridge Wells, were built around them, catering to the rich fashion of ‘taking the waters’. The Pulham Rock site says that St Blaise’s well was supposed to possess healing properties capable of curing almost everything, including:

‘ . . . the colic, the melancholy, and the vapours. It made the lean fat, the fat lean; it killed flat worms in the belly, loosened the clammy humours of the body, and dried the over-moist brain.’

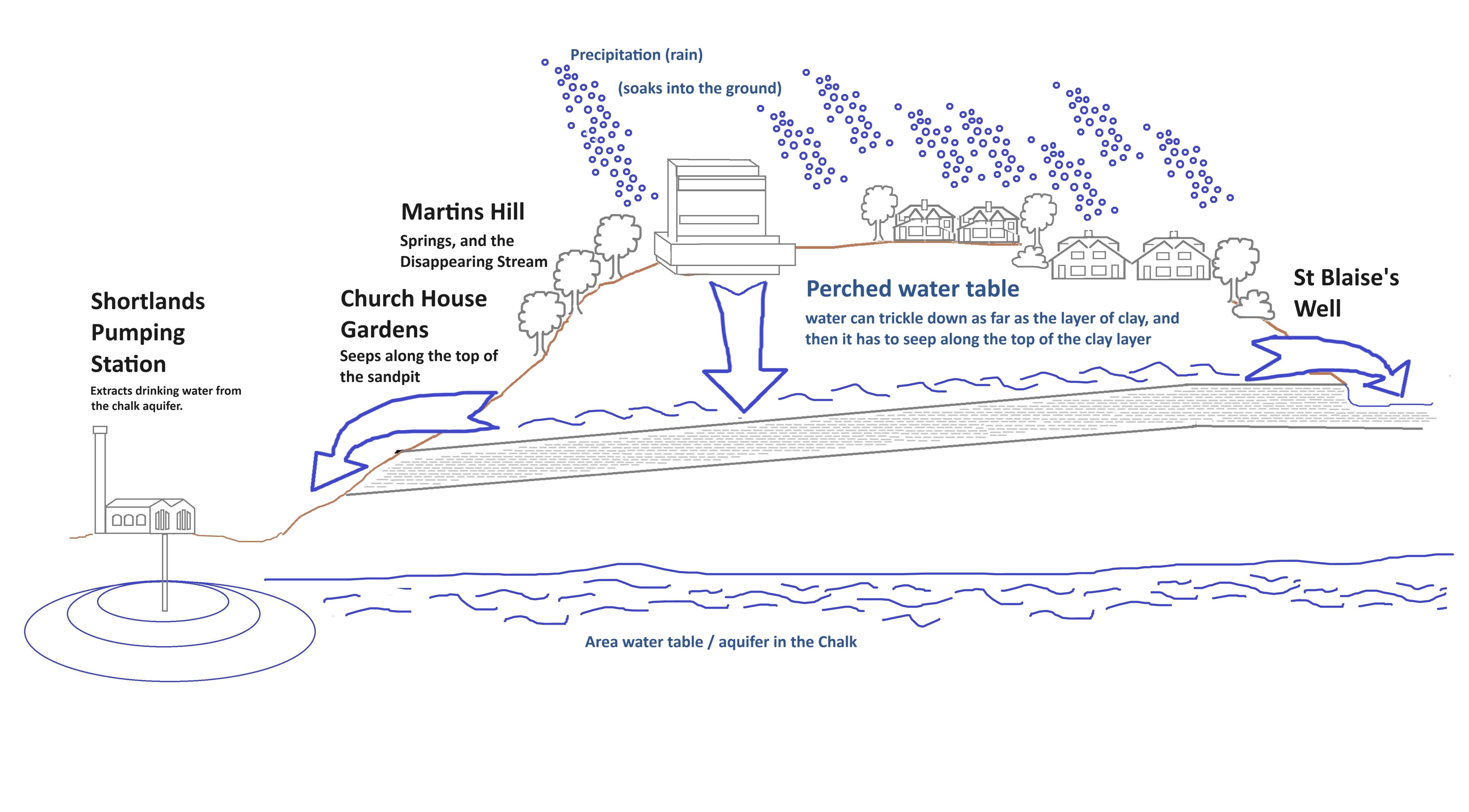

In 1754 it was roofed with thatch over 6 pillars – replaced with tile roof by the Lord of the Manor, Coles-Child, but this has not survived into modern times. The spring is chalybeate, and from a perched water table that also seeps out by Churchill Theatre and along the base of Martin’s Hill (it is why there is such a steep slope on that side of the valley).

St Blaise was the patron saint of wool carding (he was the Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia with a gruesome death) and quite popular in medieval times, when a brutal martyrdom was often popular.

The Pulhamite website describes the spring as follows:

“The Bishops built a well a few hundred yards from the chalybeate spring, and marked it with oak trees. It was about 16 inches in diameter, and the canopy had a roof of thatch, thus heightening the picturesque appearance of the scene, as shown on the left of Fig 2. The water rose so slowly, however, that it took nearly four hours to yield a gallon of water. There was an orifice in the side of the retaining wall that enabled surplus water to trickle over into the adjacent moat – or small lake – that borders the grounds of the palace. It eventually became a place of pilgrimage, and an oratory in honour of St Blaise, the patron saint of the wool trade, was built close by.

After the Reformation, however, the oratory fell into ruin, and the well into disuse, although it is not clear whether they ran out of pilgrims because they died of the colic, melancholy, the vapours or old age while they were waiting for their cups to be filled with chalybeate water, or as a result of drinking it. “

St Blaise’s well marks the site of a chalybete spring, and the water comes from a perched water table that also seeps out by Churchill Theatre and along the base of Martin’s Hill (it is why there is such a steep slope on that side of the valley). There is no visible spring nowadays, as the water table is lower (the water is pumped at Shortlands pumping station, among several local locations). The nearest place to see iron-stained waters, is the ‘hidden’ springs along the break of slope in Martins Hill. When the water table is high, iron stained water can also be found in the ditches around Norman Park.

Some photographs, old and new, of the well:

The page on the whole of Bromley Palace Park is here.

Browse our old photos, in

Browse our old photos, in  from being dominated by tower blocks: Look here and email our ward councillors about:

*

from being dominated by tower blocks: Look here and email our ward councillors about:

*