The Author, HG Wells, grew up in the upstairs of a shop on Bromley High Street. He is most famous for his prescience books The War Of The Worlds and The Time Machine. His auto-biographical writings capture a time of rapid social change in the market town.

The Author, HG Wells, grew up in the upstairs of a shop on Bromley High Street. He is most famous for his prescience books The War Of The Worlds and The Time Machine. His auto-biographical writings capture a time of rapid social change in the market town.

“His writing imagined before they existed the aeroplane, the tank, space travel, the atomic bomb and the internet. In later life, the emphasis of his political writing turned more towards the rights of the individual, and his 1940 book The Rights of Man: Or What Are We Fighting For? is a key text in the history of human rights.”(6)

“In 1895, Wells became an overnight literary sensation with the publication of the novel The Time Machine. The book was about an English scientist who develops a time travel machine. While entertaining, the work also explored social and scientific topics, from class conflict to evolution” (9)

1980s mural commemorating HG Wells in Market Square

1980s mural commemorating HG Wells in Market Square

Bertie’s parents had spent all their savings and inheritance on a china shop, Atlas House (named after ‘a figure of Atlas bearing a lamp instead of the world in the shop window. on the high street’), and it was here, on 21 September 1866 that Herbert George Wells was born. His mother, Sarah Neil had worked as a maid to the upper classes, and his father was Joseph Wells, previously a gardener, but also a professional cricket player. This shop was later demolished. It was situated just to the left of Primark’s door, though the blue plaque was moved by Primark to the Victoria Chambers building (their annexe) – it didn’t suit their decor.

“It was one of a row of badly built houses upon a narrow section of the High Street. In front upon the ground floor was the shop, filled with crockery, china and glassware and, a special line of goods, cricket bats, balls, stumps, nets and other cricket material.(8)…We lived mostly downstairs and underground, more particularly in the winter” This shop was one of a row built down the ‘New Cut’ where the High Street was straightened down an alley behind the shops on the side of market square.

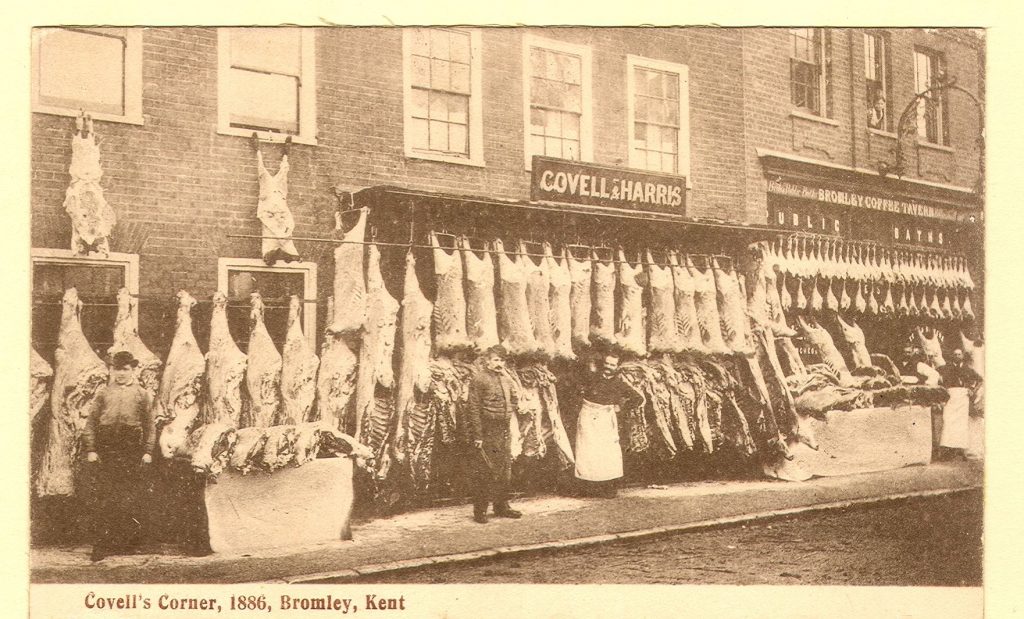

It was next door to the butchers, described by him as “… wall, separating us from the much larger yard and sheds of Mr. Covell the butcher, in which pigs, sheep and horned cattle were harboured violently, and protested plaintively through the night before they were slaughtered. Some were recalcitrant and had to be treated accordingly; there was an element of Rodeo about Covill’s yard. Beyond it was Bromley Church and its old graveyard, full then of healthy trees, ruinous tombs and headstones askew..” HG Wells also describes playing in the Rivers Ravensbourne when it was a ‘proper river’, see our post here.

[Note: Covils Butchers later built the lovely Arts and Crafts building on the corner of Market Square].

[Note: Covils Butchers later built the lovely Arts and Crafts building on the corner of Market Square].

Glimpses of the stress experienced by Victorian families who lived on ‘the knife edge between middle- and working-class’(4), can be found in what H. G. Wells wrote later about growing up in Bromley. His family ‘were so concerned with their public status that Wells was forced to fabricate stories about the extent of his family’s domestic help'(4). In prosperous times, Sarah Wells employed ‘Betsy’ to come in and char, something she herself had to do when times were hard: ‘opulent times Betsy would come in to char, and there would even be a washing day, when the copper in the scullery was lit and all the nether regions were filled with white steam and the smell of soapsuds’(8). In order to maintain the facade, ‘his mother changed after performing washing duties, whilst Wells himself was forced to keep their lack of domestic help a secret from all his friends’ (3) (4), and he says of his mother ‘Whatever the realities of our situation, she was resolved that to the very last moment we should keep up the appearance of being comfortable members of that upper-servant tenant class to which her imagination had been moulded’(8)

H.G. Wells’ mother, Sarah, ‘ran the china shop virtually single-handed handed whilst her husband played cricket for the banking families of Hoare and Norman‘. She may have neglected her housework, as Wells recalled later, but she took the full brunt of the problems and anxieties associated with taking up an unsuccessful business in which the couple had invested all their savings: “This seems a horrid business, no trade. How I wish I had taken that situation with Lady Carrick”’(6)

Charles Hoare, whom Joseph Wells trained, was the gentleman living at Kelsey Park – a ‘Senior Partner’ in the Hoare’s Bank. In addition to being a keen cricketer, and his claim to fame was establishing a coach service from Beckenham to Sevenoaks in 1869. He was the last of his family to own the estate.

He attended the Dame school in South Street, ‘off with my brother Freddy (who was on no account to let go of my hand) to a school in a room in a row of cottages near the Drill Hall, kept by an unqualified old lady, Mrs. Knott, and her equally unqualified daughter Miss Salmon, where I learnt to say my tables of weights and measures, read words of two or more syllables and pretend to do summing — it was incomprehensible fudging that was never explained to me — on a slate’(8) After this, he went to Thomas Morely’s academy, “a rather white-faced little boy in a holland pinafore and carrying a small green baize satchel for my book” (8) in the upstairs room of No. 74 High Street (old numbering). It was the school that the local “tradesmen and shopkeepers’ sent their sons to, for ‘teaching accounting and clerical skills rather than the ‘classics’”(5) and though he considered the place to be Dickensian, and his fellow students ‘poorest middle-class’, it offered him the chance to sit the exams of the College of Preceptors (Thomas Morely was a member). The advert said:

“Writing in both plain and ornamental style, Arithmetic logically, and History with special reference to ancient Egypt.” (2)

Poorer tradespeople and working class sent their boys to the Church of England National school: ‘in his youth Wells apparently scoffed at as socially inferior and a mark of social subordination’, and the pupils of both schools fell out with each-other, using the names “Morley’s Bulldogs” and “Water Rats”.

Young Bertie was free to roam out on to Martin’s Hill where he imagined soldiers charging across the slopes sending a defeated army off towards Croydon! Martin’s Hill was also the scene of real battles between the boys of Morley’s Academy (now the Frames & Art shop) where Bertie attended and the boys of the National School (which became the Parish School, now relocated to the former Quernmore school, the site was then used to build the new Methodist Church which had been demolished for the Glades).

When he was 7, in 1894, Bertie broke a leg (see details in our Queens Gardens post), which rendered him immobile in the parlour, with unheard of luxuries such as braun and jellies, crayons and books, from the mother of his “agent of good fortune, ‘young Sutton,’ the grown-up son of the landlord of the Bell”(8) who had inadvertently caused the injury. His father ‘read diversely, bought books at sales, brought them home from the Library Institute’, and thus his father brought him books to read (author’s note – the original library was in the Old Town Hall building in Market Square, quite handy for the bar, that Joseph was a regular, at The Royal Bell). After this, Bertie would devote a lot of his time to reading everything that came his way.

Queens Gardens, laid out with ornamental flower beds, the part now covered by the Glades, built in the 1990s. The cedar trees are now by the exit.

His father was ‘never really interested in the crockery trade and sold little, I think, but jampots and preserving jars to the gentlemen’s houses round about’(8) supplemented the shop income by working as a professional cricketer; he played for Kent, but this income was not steady as match payments were voluntary donations at the end of the game.

When H. G. Wells’ father broke his leg (falling from a step ladder pruning the grape he’d succeeding against the odds to flourish), the shop did not provide sufficient money to support the family, and they split up when he was 14. His mother ‘took a position’ that was live-in (so husband and children were not allowed to stay with her) so Bertie and his brothers were apprenticed to a draper in Windsor, and thus he left the area.

His mother’s employers had a library, and H. G. Wells read many of these books, and helped by this enthusiasm, subsequent to leaving Bromley, he won a scholarship to the Royal College, then the Normal School of Science, in south Kensington, at 18, and studied biology under T. H. Huxley (sometimes called Darwin’s Bulldog). He started writing fiction after graduating and becoming a science teacher. (see Birttanica.com biography)

A little note of interest: Once HG Wells became famous and prosperous, he commissioned Charles Cowles-Voysey (who built the old Magistrates Court and Town Hall extension in Bromley) to build him a house in Sandgate, Kent:

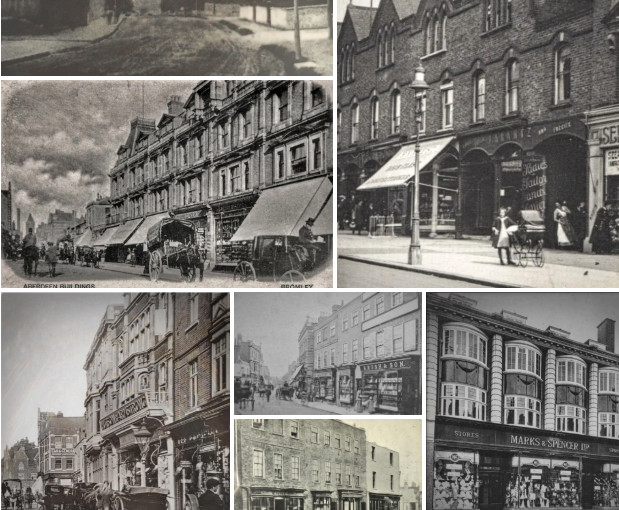

H.G. Wells commented on the social changes that he had witnessed in his young years, noting the impact from the coming of corporations and multi-branch shops to the town, on business such as the family china shop:

‘Bromley was steadily being suburbanised. An improved passenger and goods service, and the opening of a second railway station, made it more and more easy for people to go to London for their shopping and for London retailers to come into competition with the local retailers. Presently the delivery vans of the early multiple shops, the Army and Navy, Co-operative Stores and the like, appears in the neighbourhood to suck away the ebbing vitality of the local retailer. The trade in pickling jars and jam-pots died away. Fresh housekeepers came to the gentleman’s houses, who knew not Joseph (H. G. Wells’ father) and bought their stuff from the [multi-branch] stores.’(7)

Unfortunately, HG Wells had a certain amount of contempt for the place he spent his childhood, and introduces Bromley and his family’s shop as “They seem to me now quite dreadful conditions”.

H.G. Wells wrote, in a barely legible letter to Mr Heyward, a wealthy local dignitary, in 1934: “Bromley has not been particularly gracious to me nor I to Bromley and I don’t think I want to add the Freedom of Bromley to the Freedom of the City of London and the Freedom of the City of Brissago — both of which I have.” (1)

H.G. Wells described the social changes and development of Bromley in a couple of places in his writings:

‘a mindless, wasteful, anarchy which was suburbia’ when he fictionalised the growth of New Bromley in The Machiavelli (1911),

“The outskirts of Bromstead [Bromley] were maze of exploitation, roads that led nowhere, that ended in tarred fences studded with nails… It was a multitude of uncoordinated fresh starts, each more sweeping and destructive than the last, and none of them ever really worked out to a ripe and satisfactory completion.”

New Bromley is the area of ‘Bromley North conservation area’, who cottages are thought quaint and desirable, but at the time it had been a comparatively fast construction of these cottages, for working class people:

Another time, H. G. Wells describes the place as a ‘morbid sprawl of population’.

H G Wells wrote; “I am sorry I do not remember being born…” in his spidery scrawl, on a postcard to contemporary local historian William Baxter, who had apparently been badgering the author for information about growing up in Bromley.

A sad postscript: When the Labour party acquired St Marks church hall (built by subscription and bequest by the parishioners) for their Bromley headquarters, they named it after H. G. Wells. Unfortunately they sold it to developers and it has been replaced by a sky scraper. Here is the former church hall before demolition:

————————————————

(1) A letter found by Brian Philp, director of Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, tucked into an autobiography of H G Wells given to him by the daughter of Mr Heyward in 1986 (to whom it had been sent).

(2) E. L. Horsburgh Bromley Kent from the Earliest Times to the Present Century, 1980.

(3) H. G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (1934) p.73

(4) Matthew Greenhalgh, 1840-1914 Gentleman Landowners and Middle Classes of Bromley The Transfer of Wealth and Power by Greenhalgh, 1995. P97, 241

(5) Matthew Greenhalgh, 1840-1914 Gentleman Landowners and Middle Classes of Bromley The Transfer of Wealth and Power by Greenhalgh, 1995. pp97, 158

(5) Matthew Greenhalgh, 1840-1914 Gentleman Landowners and Middle Classes of Bromley The Transfer of Wealth and Power by Greenhalgh, 1995. p84

(6) https://wordsworth-editions.com/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-hg-wells

(7) H. G. Wells, New Machiavelli (1911) pp. 44-45.

(8) H. G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography (1934) ch.2

Browse our old photos, in

Browse our old photos, in  from being dominated by tower blocks: Look here and email our ward councillors about:

*

from being dominated by tower blocks: Look here and email our ward councillors about:

*